First Generativity Project

There is a bulging 9x12 envelope, sealed with bright red tamper-resistant security tape, sitting on my desk. I will never open it. I will hand-deliver the envelope within a month of a death. And that will be the end of a project that started months before.

Finally, after a couple of false starts, I conducted my first Generativity Project in the style of Chochinov’s Dignity Therapy. It took a couple of weeks to complete. Here, I detail my fits and starts as well as the process and tools I eventually settled on.

Dignity Therapy, developed and empirically tested by Max Chochinov, has a protocol proven to increase dignity in terminal patients, and the resulting generativity document has been shown to provide great solace to the people left behind. Generativity refers to the fact that the document is meant as a message from an older generation to younger and future generations. The protocol, example interviews, and sample final documents are discussed in accessible detail in Chochinov’s Dignity Therapy: Final Words for Final Days. The book also addresses how to handle situations where a subject has few words, struggles to articulate thoughts, or shares stories or statements that could be hurtful to the intended recipients. There are many other suggestions in the book that help with both the interviewing process and the editing process.

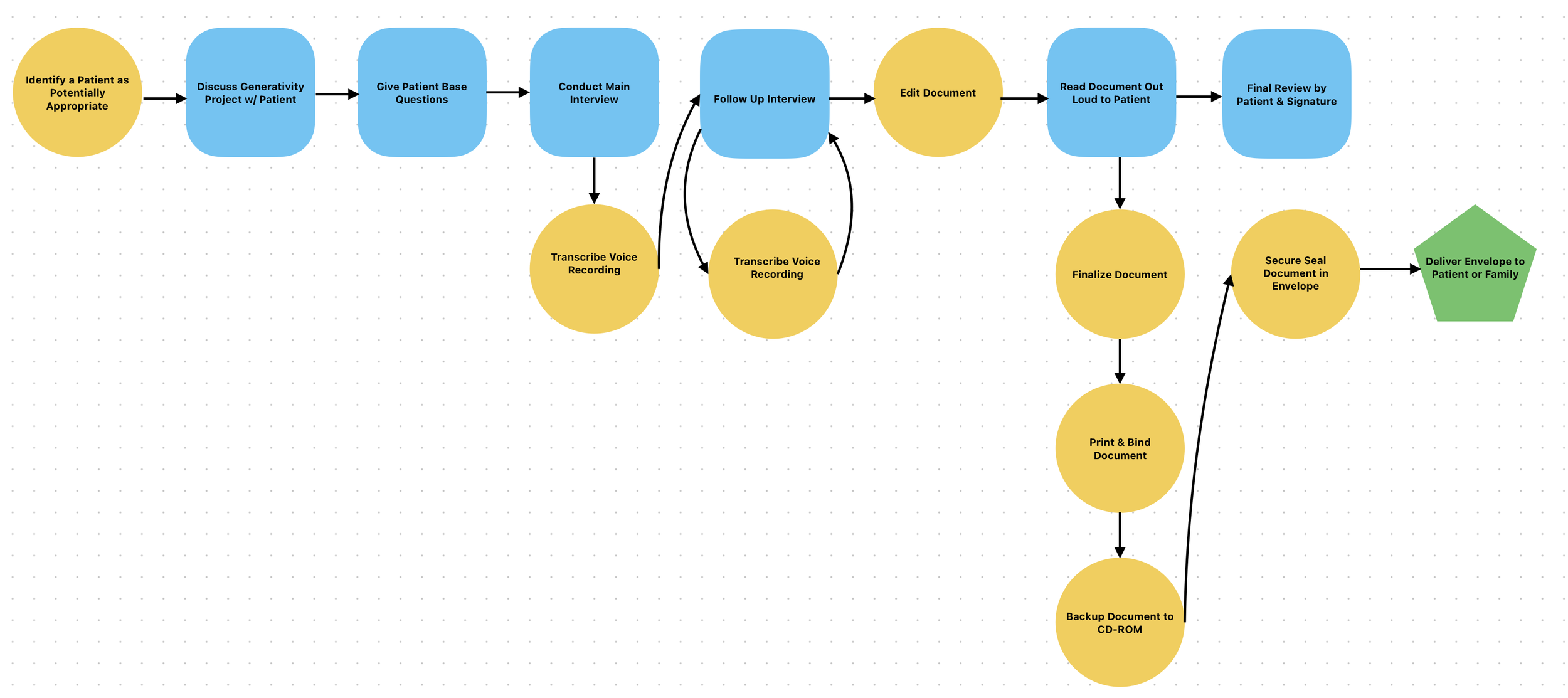

At the 10,000-foot view, the process is straightforward.

The Generativity Project Workflow: These steps ensure that the final document is exactly what the subject wants to give to family and friends.

First, a compiler gathers pertinent information about the potential subject to determine whether it is appropriate to suggest the generativity process. For instance, subjects must be likely to live at least two more weeks in order to complete the process. They must also be able to communicate by spoken word and have their mental faculties and memories largely intact. The compiler can’t complete the protocol if the subject dies before two weeks have passed, and the subject can’t provide meaningful information if cognitively impaired, as with moderate to severe dementia. The first person with whom I was able to successfully complete the project was crystal clear mentally and was not actively in the dying process.

“Strive not to be a success, but rather to be of value.”

Next, the interviewer meets with the patient to determine whether the subject would benefit from the process and whether they are interested in doing a generativity project. Some subjects aren’t ready because they can’t yet engage in an activity whose premise is that their time on Earth is severely limited. Others may lack the energy or feel too unwell to focus. My subject was able to speak clearly, had the stamina for an hour-long conversation, and had reached acceptance of her condition. She was readily able to talk about it.

If the subject will benefit and is interested, the compiler explains the entire protocol, including the base questions, and answers any concerns. Then they arrange a time to meet for the main interview. The subject may keep a list of the main questions to consider how they want to respond. My subject was immediately interested and was pleased with both the process and the promised work product—a document she could leave to her children.

At the time of the main interview, the compiler brings equipment to record everything the subject says so it can be transcribed later. The transcription is then lightly edited and compiled into the penultimate generativity document. Sometimes the compiler conducts a follow-up interview to clarify unclear statements or expand overly terse comments. I met with my subject twice. The first time, I got through all the protocol questions and follow-ups. I returned once more to clarify and expand a few topics. I found that a high-quality wireless mic for clear voice recording is essential. There are many small microphones that easily attach to clothing and connect to a smartphone used as a voice recorder.

In the next meeting, the compiler reads the document aloud to the subject, who provides feedback and changes. The subject has the final say, as it is their document. Some want to preserve their unique tone; others prefer more of a biographical style or personal-letter format. Sometimes a family member’s presence helps correct dates, places, and timelines. My subject was clear about how she wanted to phrase things and appreciated that I preserved her tone and speech patterns. Her son listened and was able to correct some dates and places she had mixed up.

“These same experiences make of the sequence of life cycles a generational cycle, irrevocably binding each generation to those that gave it life and to those for whose life it is responsible. Thus, reconciling lifelong generativity and stagnation involves the elder in a review of his or her own years of active responsibility for nurturing the next generations, and also in an integration of earlier-life experiences of caring and of self-concern in relation to previous generations.”

Once the changes have been made and the document is finalized, the compiler prints it and delivers it to the subject for one last review. The subject then decides what they want done with it. Some ask the compiler or another trusted person to hold the document until death and then deliver it to a chosen family member or friend. Others prefer to give it to their loved ones immediately. My subject wanted me to hold on to it and deliver it to her son after her death.

Along with the protocol, the compiler must also make decisions about speech-to-text transcription, maintaining the subject’s privacy, securing the document, drafting a written agreement, and determining the exact form of the final document in both hard-copy and digital formats.

In the original protocol, human transcribers were employed. Because the cost of human transcription is currently exorbitant and the turnaround slow, I use speech-to-text algorithms. It took several attempts to find a reliable method for capturing clear audio using a smartphone. Small, good-quality microphones are key. My first few attempts yielded audio too unclear for automated transcription. I eventually found a “rig” that works for me. I’ll outline that in another article.

Another important aspect of this work is the personal nature of the questions and answers. A written agreement between subject and compiler is essential to ensure both feel protected and safe. The subject must agree to be recorded. The compiler must agree to protect the subject’s privacy. Both parties need the ability to end the project at any time. The subject’s wishes regarding the final document must be recorded. And if the subject wants the compiler to deliver the document after their death, the compiler must ensure the document is secure and that the security can be demonstrated. Family or friends may want reassurance that their loved one agreed to participate and that the generativity document truly represents their words. For all these reasons, a written agreement is a must as are security and privacy protocols.

I had a couple of false starts before everything came together. And although I initially thought the document should be a complete surprise to the recipients, I discovered great benefit in having at least one close family member know about the project and sit in on the penultimate review. Legally, it's good to have a witness confirming the subject was not coerced. Also, another family member can help correct dates, locations, and other details that often get mixed up. Most subjects are older and ill, making these kinds of errors common.

“Your legacy is every life you touch.”

While working on this project, I fretted because some of the things my subject focused on were not things I would have emphasized. Conversely, there were topics I would have elaborated on that she mentioned only briefly, despite being encouraged to expound further. I felt strange editing the document for penultimate review, and as I read it aloud with her son listening a few feet away, I worried he would feel the same way I did. I imagined him being disappointed. But I kept reading, making her requested changes, and correcting dates and timelines with her son’s input.

After I finished, I asked, “What do you think?” I held my breath. My subject nodded and said, “That sounds perfect.” I barely heard her; I was too focused on her son. He stared at me for a few seconds, his mouth opening slowly. I braced myself. Then he finally spoke.

“I don’t know what to say,” he said, pausing again. My blood pressure rose. Then a torrent of words:

“That is amazing. You’ve captured my mom perfectly! And I learned things about her I never knew. I feel more connected to her in so many ways. This is incredible! Thank you!” He continued telling me how much the document meant to him and how cherished it would be by the entire family. I breathed a sigh of relief.

I think it was hard for me to appreciate how differently people communicate and how families operate under different conversational norms. The experience reaffirmed for me the importance of preserving the subject’s voice, tone, enthusiasm, and communication style.

“Carve your name on hearts, not gravestones. A legacy is written into the minds of others and the tales they share about you. ”

Afterward, I went home and printed the completed document on archival paper, then bound it with a black poly cover on the front and back, held together with decorative bolts. I also placed a PDF file of the final version, a README file, and an explanation of what a generativity project involves and its purpose in an archive folder and burned them to a thumb drive. The thumb drive is formatted to behave like a CD or DVD-ROM. This protects the files, and short of reformatting the drive, they should remain secure until my involvement ends—when I hand the document to the designated family member.

The last thing I did was to have the subject sign the final version in a section affirming that these are their words, that they fully approve the document, and that they allow it to be shared with their family. Both the drive and the document were placed in a secure envelope sealed with tamper-evident tape. That envelope now sits on my work surface, waiting to be delivered—a constant reminder of the revelatory journey I went on with my patient. Not only did she communicate messages of love to those she will leave behind, but I learned more about her, the things she was most proud of, and her essence as a person.

It is always an honor to spend time with someone who has little time left. But completing a generativity project feels vastly different from simply talking, even if the conversations cover the same content. I think it’s because I get to help create a message for survivors and future generations in that family, and I can enhance a person’s ability to communicate with their progeny. I will certainly do more of these projects. As I continue, I will refine the process and the tools I use. But for now, I am grateful to have gone on this journey with my patient, and I feel more connected to her life.